Bradycardia Overview

What is bradycardia? The National Institutes of Health defines bradycardia* as a heart rate <60 bpm in adults other than well-trained athletes.9 The determination on whether or not treatment is necessary for bradycardic events is generally based on the presence of bradycardia symptoms. The clinical manifestations of bradycardia can vary widely from insidious symptoms to episodes of frank syncope.5

Common bradycardia symptoms include:

- syncope

- presyncope

- transient dizziness or lightheadedness

- fatigue

- dyspnea on exertion

- heart failure symptoms

- or confusion resulting from cerebral hypoperfusion11

Bradycardia can stem from either sinus node dysfunction (SND) or atrioventricular block (AVB).

SND, historically referred to as sick sinus syndrome, is most often related to age-dependent, progressive, degenerative fibrosis of the sinus nodal tissue and surrounding atrial myocardium.6 Abnormalities of the sinus node, atrial tissue, atrioventricular nodal tissue, and the specialized conduction system can all contribute to bradycardia, discordant timing of atrial and ventricular depolarization, and abnormal ventricular depolarization.5

The electrocardiographic findings in patients with SND are varied and the diagnosis may be considered in patients with sinus bradycardia or atrial depolarization from a subsidiary pacemaker other than the sinus node (i.e. ectopic atrial rhythm, junctional rhythm, or ventricular escape), intermittent sinus pauses, or a blunted heart rate response with exercise (chronotropic incompetence).3 Chronotropic incompetence represents failure to reach a target heart rate with exertion that is inadequate to meet metabolic demand.5

The clinical manifestations of atrioventricular block will also depend on whether the atrioventricular block is fixed or intermittent and the ventricular rate or duration of ventricular asystole associated with atrioventricular block.5

Using the Bradycardia with a Pulse Algorithm for Assessment

The Bradycardia with a Pulse Algorithm is a set of steps for assessing and treating patients with symptomatic bradycardia, a condition where the heart rate is below 50 beats per minute. It is crucial for providing structured and efficient patient assessment in clinical settings, allowing healthcare providers to systematically evaluate the patient’s heart rate, rhythm, and perfusion status. By following this clear protocol, clinicians can quickly determine if a patient is experiencing adequate or inadequate perfusion, which can directly influence treatment options. The bradycardia algorithm’s structured approach minimizes misdiagnosis risk, enables timely intervention, and ultimately leads to better patient outcomes.

Bradycardia with a Pulse Algorithm Steps

Steps to assess and manage bradycardia with a pulse algorithm usually involve the following, as referenced on our ACLS Bradycardia site:

- Assess clinical condition – Start by checking the patient’s heart rate and rhythm using an ECG or pulse monitor.

- Identify and treat the underlying cause – Maintain the airway and provide oxygen as needed, while placing the patient on cardiac monitors to assess rhythm, blood pressure, and oxygen saturation. Obtain a 12-lead ECG, establish IV access, and determine if the bradycardia is the cause of symptoms or due to another illness, treating any underlying issues accordingly.

- Is the persistent bradyarrhythmia causing symptoms? – Determine if the bradyarrhythmia is causing symptoms or signs due to poor perfusion. Common symptoms are hypotension, altered mental state, chest discomfort, shock, or acute heart failure.

- If not, monitor and observe – Consider observation and possible pharmacological options, if necessary.

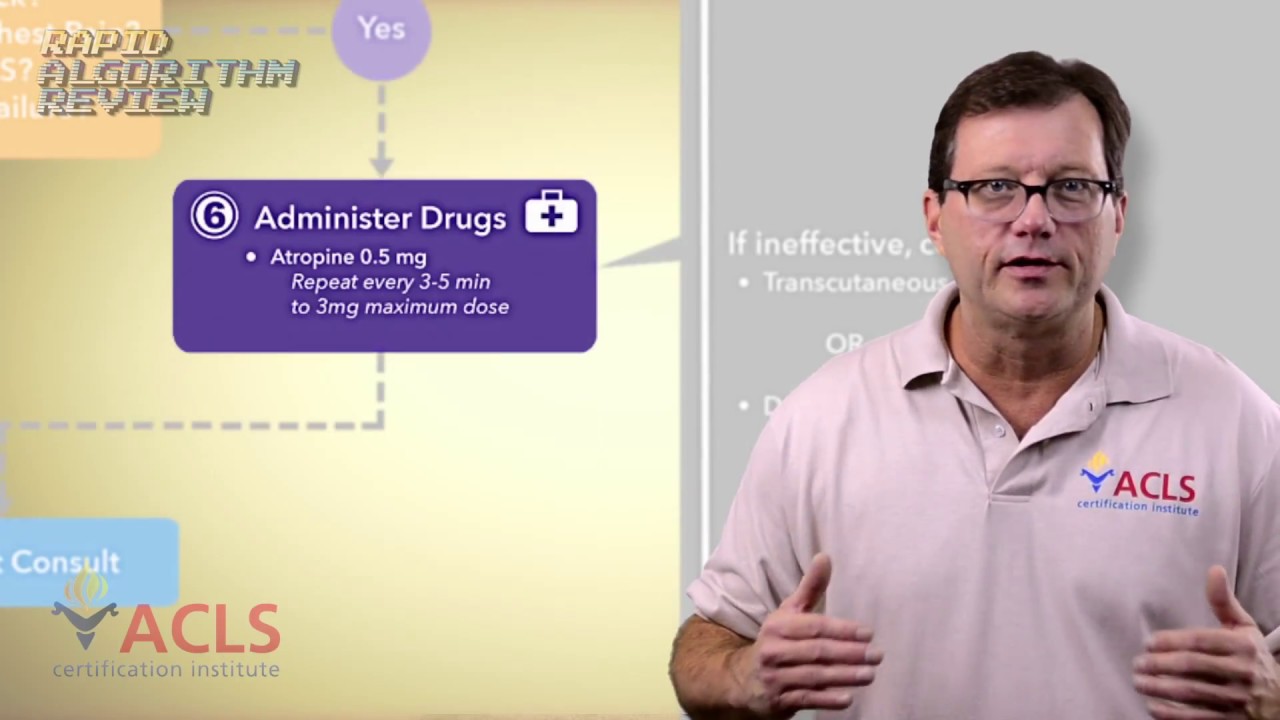

- If yes, administer drug treatment – If the patient has poor perfusion, administer .5 milligrams of atropine through the IVP (IV push) every three to five minutes until a maximum of three milligrams have been given. If the atropine is ineffective, implement transcutaneous pacing or administer a dopamine infusion of 2 to 20 micrograms per kilogram per minute or an epinephrine infusion of 2 to 10 micrograms per minute. Titrate to the patient’s response.

- Other considerations – Consider transvenous pacing while consulting with an expert for further diagnosis and treatment.

Bradycardia Evaluation

When a patient is evaluated for symptomatic bradycardia, an in-depth history and physical is important, along with the identification of possible reversible causes. The following is a list of conditions associated with bradycardia and conduction disorders:11

- Autonomic dysfunction

- Carotid sinus hypersensitivity

- Neurally-mediated syncope

- Situational syncope

- Cardiomyopathy

- Ischemic

- Non-ischemic

- Infiltrative

- Congenital heart disease

- Degenerative

- Infection

- Lyme disease

- Infectious endocarditis

- Chagas disease

- Ischemia/ infarction – especially inferior MI

- Medications/ drugs

- Antihypertensives – Beta-blockers, verapamil, diltiazem

- Antiarrhythmics – Amiodarone, dronedarone, Sotalol, digoxin

- Psychoactive – Phenothiazines, opioids, tricyclic antidepressants

- Metabolic/ endocrine

- Acidosis

- Hypo- or hyperkalemia

- Hypothyroidism, hypoadrenal state

- Hypothermia

- Hypoxia

- Rheumatologic

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Scleroderma

- Lupus

- Surgical/ traumatic

- Catheter ablation

- Surgical correction of congenital heart disease

- Valve surgery

- Septal myectomy/ alcohol septal ablation

Evaluation Options

ECG

Further testing of patients with bradycardia after the initial history and physical should include a 12-lead ECG, which might suggest structural heart disease, conduction disturbance, or other cardiac conditions that may predispose patients to bradyarrhythmias.7

Ambulatory ECG monitoring

Can be considered to establish a diagnosis or make a symptom-rhythm correlation, with longer-term monitoring resulting in higher yield.2

Exercise Testing

Although not routinely recommended for assessment of ischemia, exercise testing can be considered in patients with symptoms temporally related to exercise, asymptomatic second-degree AV block, or for suspected chronotropic incompetence.11

Transthoracic Echocardiogram

Recommended to evaluate patients with new left bundle branch block, Mobitz type II AV block, high-grade AV block, or complete AV block.5

Sleep Apnea Screening

Patients who screen positive should be considered for polysomnography and/or specialty consultation. The prevalence of sinus bradycardia in patients with sleep apnea can be as high as 40%, with episodes of second- or third-degree AV block in up to 13% of patients.8

Symptomatic Bradycardia Treatment

A bradycardic rhythm is most often treated only when symptoms are present. If reversible causes aren’t immediately identified and/or if reversing the cause is taking too long, pharmacologic interventions are the first-line approach for bradycardia treatment. Atropine 0.5 mg intravenous (IV) is given up to a total of 3 mg.1 Atropine sulfate acts by reversing the cholinergic-mediated decreases in the heart rate and AV node conduction.1

If atropine is ineffective, two treatment pathways are available. The patient’s heart can be paced either intravenously or transcutaneously (TCP), or more emergency medicine can be given. The two pharmacologic choices are dopamine 2 to 20 mcg/kg/min and/or epinephrine 2 to 10 mcg/min.1

If no response occurs after atropine boluses, epinephrine, and/or dopamine infusions, pacing is initiated. Transcutaneous pacing should be limited to bridging to transvenous pacing in patients acutely or critically ill due to the painful nature of the therapy and difficulty establishing and ascertaining consistent myocardial capture.11 One of the most important steps when a patient is paced is to ensure there is electrical and mechanical capture.1 Without mechanical capture, the cardiac muscle is not electrically depolarized to threshold and no muscle contraction will occur. The safety of temporary transvenous pacing has improved with balloon-floatation catheters when placed by experienced operators.1

Permanent pacemaker implantation is the definitive treatment for a patient with chronic symptomatic sinus node dysfunction. This includes patients who are on heart rate lowering medications that are clinically necessary when there is no alternative therapy.11 In patients with Mobitz type II second-degree AV block, high-grade AV block (greater than 2:1), or complete AV block, there is some evidence of improved survival with the placement of a permanent pacemaker.10 Permanent pacing is also warranted in patients with AV conduction system disturbance in disease processes with a more rapidly progressive nature.11

*Bradycardia and symptomatic bradycardia are topics so in-depth that it is impossible to review the types, causes, and treatments exhaustively. For the purpose of this article, the “2018 ACC/AHA/HRS Guideline on the Management of Patients With Bradycardia and Cardiac Conduction Delay” is referenced, and readers are encouraged to review the complete guideline.

Sources

- American Heart Association. Advanced cardiovascular life support provider manual. 2016.

- Barrett PM , Komatireddy R , Haaser S , Topol S , Sheard J , Encinas J , et al. Comparison of 24-hour holter monitoring with 14-day novel adhesive patch electrocardiographic monitoring. Am J Med. 2014; 127(95):e11-95.e17.

- Brubaker PH, Kitzman DW. Chronotropic incompetence: causes, consequences, and management. Circulation. 2011;123:1010–20.

- Epstein AE, DiMarco JP, Ellenbogen KA, et al. 2012 ACCF/AHA/HRS focused update incorporated into the ACCF/AHA/HRS 2008 guidelines for device-based therapy of cardiac rhythm abnormalities: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/ American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:e6–75.

- Kusumoto FM, Schoenfeld MH, Barrett C, Edgerton JR, Ellenbogen KA, Gold MR, et al. 2018 ACC/AHA/HRS guideline on the evaluation and management of patients with bradycardia and cardiac conduction delay. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Oct 31. pii: S0735-1097(18)389848.

- Lev M. Aging changes in the human sinoatrial node. J Gerontol. 1954;9:1–9.

- Linzer M, Yang EH, Estes NA, Wang P, Vorperian VR, Kapoor WN, et al. Diagnosing syncope. Part 1: value of history, physical examination, and electrocardiography. Clinical efficacy assessment project of the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126:989–96.

- Mehra R, Benjamin EJ, Shahar E, Gottlieb DJ, Nawabit R, Kirchner HL, et al. Association of nocturnal arrhythmias with sleep-disordered breathing. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006;173:910–16.

- National Institutes of Health. Pulse. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/003399.htm. Accessed December 21, 2019.

- Shaw DB, Kekwick CA, Veale D, Gowers J, Whistance T. Survival in second degree atrioventricular block. Br Heart J. 1985;53:587–93.

- Sidhu S, Marine JE. Evaluating and managing bradycardia. Trends in Cardiovascular Medicine. https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.tcm.2019.07.001.

Dan Bunker DNAP, MSNA, CRNA —Dan has worked in the healthcare industry for nearly 30 years. He worked as a registered nurse in the coronary care ICU for 7 years and was a flight nurse with Intermountain’s Life Flight for nearly 10 years. He has been a certified registered nurse anesthetist (CRNA) for 11 years, working in the hospital setting as well as maintaining his own private practice. In addition, he is a professor in the nurse anesthesia program at Westminster College in Salt Lake City, Utah. He has served in various leadership roles within the Utah Association of Nurse Anesthetists (UANA) and is currently the president-elect.

Recommended Articles

Bradycardia Algorithm Video

Review the bradycardia algorithm in just 2 minutes with our quickfire video review!